First survey published with ocular manifestations associated with COVID-19 conducted by doctor Jorge Alió and doctor Amesty

First survey published with ocular manifestations associated with COVID-19 conducted by doctor Jorge Alió and doctor Amesty

In March 2020, Wu and colleagues published in JAMA the first report on the presence of ocular symptoms in patients with COVID-19.

Signs of conjunctivitis were seen in about 32% of a group of 38 hospitalized patients, the severity of which was directly correlated with the severity of the COVID-19 infection. The most common symptoms included hyperemia, tearing, chemosis and mucous discharge. Conjunctival samples of 11 patients were tested, and two were found positive for histological signs of the viral infection.

This study was a first warning of the potential risk for infection through tears and other ocular secretions and raised the issue of how eye care professionals should protect themselves from the risk of contracting the disease.

Several other reports followed, which included not only conjunctivitis but also other ocular manifestations, such as uveitis, episcleritis and retinal abnormalities. Overall, the reported prevalence of ocular manifestations varied between 0.8% and 31.6%, depending on the study design.

To date, although the association of COVID-19 with ocular phenomena appears to be relatively common, no causative relationship has been confirmed. However, research is ongoing, supported by a growing body of raw data.

“Immunohistochemical analysis has confirmed that ACE2 and TMPRSS2, the key factors for cellular susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2, are expressed in the ocular surface cells. This indicates that the eye is indeed susceptible to infection by SARS-CoV-2 and highlights the importance of protecting this region from contamination. It is also a warning for us because, as ophthalmologists, we are exposed to being infected through close contact with the eyes of our patients,” Jorge L. Alió, MD, PhD, said.

Some months ago, Alió created a questionnaire and launched a survey on the observation of COVID-related ocular manifestations by ophthalmologists. Through Healio.com, email contacts, newsletters and website announcements by national and international ophthalmology societies, the questionnaire reached a high number of ophthalmologists worldwide, providing an interesting picture of how frequently ophthalmologists encounter ocular manifestations potentially related to COVID-19, what signs and symptoms they found, and how they treated them.

“No other platform has such a wide reach as Healio.com. This allowed us to obtain global information that we are now making available to a global audience. The project also gained the attention of Théa, which offered unrestricted support toward its accomplishment,” Alió said.

Conjunctivitis most common manifestation

A total of 234 eye care professionals from 32 countries in six continents answered the questionnaire (Figure 1). The majority (56.9%) were specialized ophthalmologists, and all subspecialties were represented. Of them, 39% reported visiting patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. The test most commonly used to confirm the COVID-19 diagnosis was PCR alone in 64% of the cases or combined with serology in 22.5% of the cases. COVID-19 was classified as mild in 63.6% of the cases, moderate in 25% and severe in 11.4%.

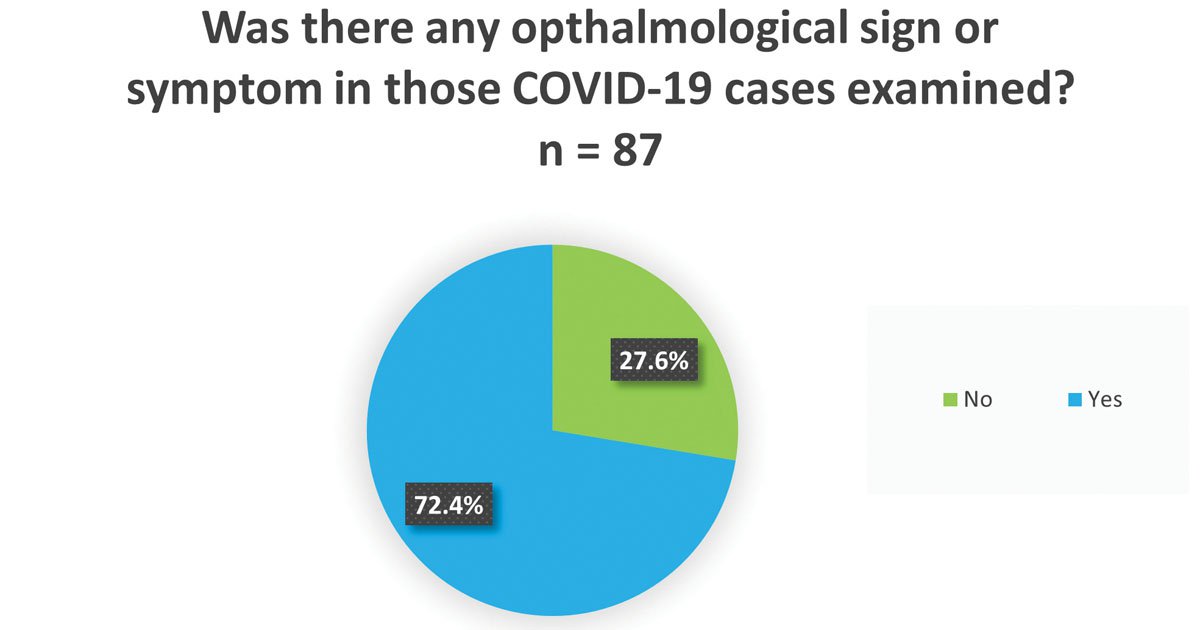

Ocular signs and symptoms possibly related to COVID were reported by 72.4% of respondents and were seen in one to three cases by 64.8%, in three to 10 cases by 25.3% and in more than 10 cases by 10% (Figure 2). The most common finding was conjunctivitis, identified by 47.8% of respondents, followed by anterior uveitis by 8.9%. Another 8.9% reported not otherwise classified problems, and 34.4% saw no anterior segment sign (Figure 3). No posterior segment sign was identified by the majority of respondents (79.7%), but some cases of optic neuritis, posterior uveitis, retinitis and other posterior segment changes, such as retinal detachment, branch retinal vein occlusion, central retinal artery occlusion and vasculitis with intraretinal hemorrhage, were identified. Anterior uveitis was often associated with retinitis, in one case with optic neuritis and in one case with posterior uveitis.

“The survey confirms what was found by the studies published so far, that ocular surface symptoms, and conjunctivitis in particular, are the most common manifestation in the eyes of patients with COVID-19,” Alió said.

COVID-19-related conjunctivitis, he said, has two different etiologies and presentations. The first, occurring early in the disease, is related to direct virus infection. It is a form of follicular conjunctivitis, and the swab shows presence of SARS-CoV-2 in conjunctival secretions. The second is usually just hyperemia presenting later in the course of the disease and is likely to be a secondary immune reaction, an inflammatory complication of the disease due to the release of cytokines. The PCR test on the conjunctiva and tears, in this case, is negative. Both types of conjunctivitis are benign and self-limiting and do not cause the long-term sequelae of other types of viral conjunctivitis, such as herpes or adenovirus.

“Reassuringly, COVID-19 is not a sight-threatening disease. You can suffer from external eye disease and can transmit the infection from conjunctiva and tears, but the sequelae are not blinding,” Alió said.

In the survey, 68.5% of respondents reported no signs or symptoms of vision loss related to ocular findings overall.

Retinal cases may be underreported

“We must consider that ocular manifestations are likely to be underreported because COVID-19 patients are hospitalized or isolated at home, and ocular manifestations are mostly not severe enough to require our consultation,” Alió said.

Particularly, the true prevalence of posterior segment manifestations is difficult to estimate because only a small number of researchers have had the chance to examine the ocular fundus or to perform posterior segment OCT on patients with COVID-19.

“Retinal changes, including hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, dilated veins and vasculitis, have been reported in studies, but it is not clear if they are the sign of direct damage from SARS-CoV-2 or the consequence of immune response or comorbidities,” Alió said.

Theoretically, due to the cytokine storm induced by the disease, a more significant impact on the vascularized structures of the eye would be expected, while the number of reported cases of vasculitis and vascular occlusion is surprisingly low.

“This is a positive sign. COVID-19 is much more benign for the eye than we expected,” he said. “However, more evidence and elucidation on posterior segment involvement is needed and is a future goal of research.”

Treatment

COVID-related ocular manifestations were mostly treated with topical medications by 54% of respondents. Only 2.4% used systemic medications, and 14.9% used both. No medications were used in 28.7% of the cases (Figure 4).

Conjunctivitis was mostly treated with topical steroids, antibiotics or a combination of the two, with the addition of lubricants, artificial tears or cold compresses in some cases. Uveitis was mainly treated with corticosteroids, NSAIDs and mydriatics, and two respondents mentioned the additional use of antiseptics with virucidal activity. Episcleritis was treated with antibiotics, vasculitis with systemic steroids, retinal detachment with surgery and branch retinal vein occlusion with intravitreal injections. One case of central retinal artery occlusion was classified as COVID-induced, but no treatment was performed.

“So far, treatment protocols for COVID-related ocular manifestations do not differ significantly from our standard protocols. COVID-related conjunctivitis is treated in the same way as viral conjunctivitis, with supportive treatment to minimize discomfort. To address the inflammatory component, I use soft corticosteroids such as Softacort (Théa Pharmaceuticals) or FML (Allergan) because there is no need for deep penetration by high-power steroids. I also recommend cold compresses and hygiene measures, such as not touching the eyes and keeping them clean with saline. I do not use antivirals,” Alió said.

Risk of transmission

Ophthalmologists are in the high-risk category for COVID-19 infection. A study carried out in an ophthalmology department in Granada, Spain, showed that 16% of the ophthalmic personnel had contracted the disease by August 2020.

“Since then, we have learned more on how to protect ourselves with masks and also eye protection because the eye is a port of entry for the virus. Goggles and face shields, however, cannot be used during ophthalmic examinations, and we must be aware that the risk for us will never be zero,” Alió said.

However, the protection granted by vaccination will give ophthalmologists the opportunity to examine patients better and more frequently, to enter COVID wards for consultations on ocular problems and to do research.

“Gathering data is important, and the survey we have launched has been an important step in this direction because it reached ophthalmologists in every continent,” Alió said.

As the coronavirus pandemic sickened more and more people, ophthalmologists wondered about the effects on the eye and were concerned about possible eye sequelae and vision loss.

“Our survey, as well as the many papers published over this first year, are fairly reassuring in this respect. The disease does not seem to affect vision, and ocular manifestations are mainly limited to the ocular surface, can be treated easily and do not cause vision-threatening sequelae,” Alió said.

However, even if COVID-related ocular manifestations are no big concern, virus transmission through the eye is, and awareness about this should be raised, not just among ophthalmologists, but in the general population, Alió said. – by Michela Cimberle

References:

- Amesty MA, et al. Ophthalmol Ther. 2020;doi:10.1007/s40123-020-00260-y.

- Benito-Pascual B, et al. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;doi:10.1080/09273948.2020.1792512.

- Bertoli F, et al. J Ophthalmol. 2020;doi:10.1155/2020/4827304.

- Brandão-de-Resende C, et al. Lancet. 2020;doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31918-8.

- Domínguez-Varela IA, et al. Infect Dis (Lond). 2021;doi:10.1080/23744235.2021.1882697.

- Jevnikar K, et al. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;doi:10.1080/09273948.2021.1896008.

- Jin YP, et al. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021;doi:10.1177/1120672121992949.

- Kumar KK, et al. Ind J Ophthalmol. 2021;doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_3037_20.

- Lacorzana J, et al. Med Clin (Engl Ed). 2020;doi:10.1016/j.medcle.2020.05.014.

- Nasiri N, et al. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2021;doi:10.18502/jovr.v16i1.8256.

- Sánchez-Tena MÁ, et al. J Clin Med. 2021;doi:10.3390/jcm10071340.

- Wan KH, et al. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.5819.

- Wu P, et al. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.1291.

For more information: Jorge L. Alió, MD, PhD, can be reached at Miguel Hernandez University and Vissum Miranza, C/ Cabañal 1, 03016 Alicante, Spain; email: jlalio@vissum.com.

Published in healio.com